Weather Events

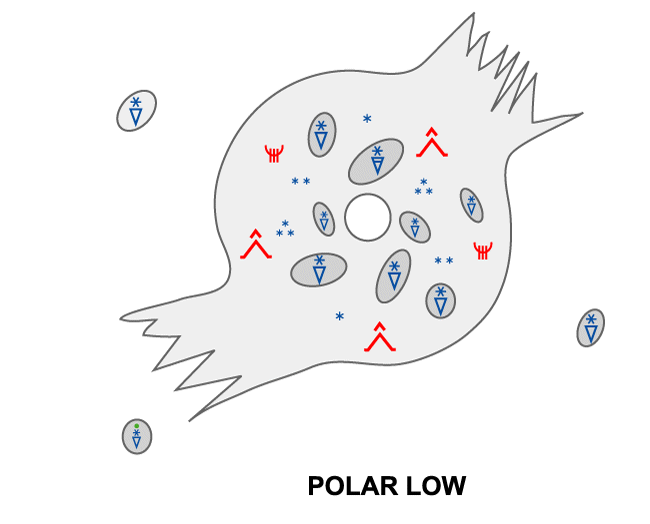

A polar low is normally embedded in a southerly moving air mass, and generally the wind is strongest on the western half of the low where the circulation of the low has the same direction as the ambient large scale wind. The most dangerous aspect of a Polar Low is the sudden onset of wind and snow which occurs in the shear zone from the eye or the more tranquil eastern side of the low to the western or northern windy side. Fishermen describe the wind as increasing from almost quiet to storm force in just a few minutes. On average, max observed wind is 21 m/s (severe gale), but about one in four have storm force winds. The strongest polar low recorded had more than 35 m/s over a 12 hour period.

In modern times, casualties are rare in the fishing fleet, but damage to vessel or fishing equipment is common for those caught unprepared. More indirectly, Polar Lows can deposit a lot of snow inland from the coast, and avalanches related to polar lows have taken several lives in recent years.

Because of the strong winds and sharp shear zones as well as strong updrafts and downdrafts, aircraft flying in the vicinity of a polar low are subjected to moderate to severe icing and turbulence. Air traffic is usually suspended during PL events.

Normally the precipitation is in the form of snow or hail showers, but since the surface temperature of the marine air mass in which the low is embedded tends to approach the same as the SST, the 2m temperature can be well above freezing. The air mass is in general quite cold so it takes some time for the snow to melt, and so it is not uncommon to have snow even if T2m are as high as 3°C. In polar lows at lower latitudes, e.g. at the North Sea Coast, T2m is often higher than this, and rain or sleet should be expected at sea level.

After landfall Polar Lows quickly lose their intensity, since the supply of heat from the sea surface is cut off. The wind then quickly subsides, but the precipitation can persist and be quite strong for up to 100 km inland.

Table of weather

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Precipitation |

|

| Temperature |

|

| Wind |

|

| Other relevant information |

|

Vessel icing

Icing on ships is most common north of 73 degree north where the sea surface and air temperatures are low. In such cases, severe vessel icing is common in Polar Lows.

Since the polar icecap during the latter part of the winter often extends all the way south to the Bear Island at 74'30'' north, icing can occur all the way down to the northernmost coast of Scandinavia (Finnmark) in northeasterly cold air outbreaks from the Franz Josef's Land area.

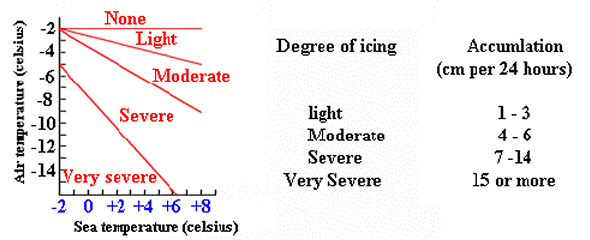

The chart (Mertins 1968) below shows a simplified graphic over vessel icing in gale force winds (Beaufort 8). Icing naturally increases with wind speed and wave height, the latter increasing with the distance from the ice edge.

Figure 5.2: A Mertins diagram over icing vs. sea and air temperature with wind of gale force. Similar diagrams must be used for other ranges of wind speeds

Impressions of the polar low on the ground

Figure 5.3: Cancelled flight due to a polar low in Hammerfest. Business no longer as usual... Photo: Arnstein Jensen/NRK

Figure 5.4: A combination of wind, windblown snow and and heavy snowfall gives severely reduced visibility and often very difficult driving conditions as Polar Lows make landfall. Disruption of both marine and air traffic is common. Photo: Gunnar Noer

Figure 5.5: A polar low as seen from the inside, the eyewall approaching. Photo: Gunnar Noer

This shear zone is the reason why polar lows are feared in the coastal fisheries. The wind is commonly reported to increase from calm to storm force winds in less that 10 minutes. Waves are observed to increase rapidly in a similar time span, with difficult and confused wave conditions as a result of rapidly changing wave and wind directions.