Kármán Vortex Streets

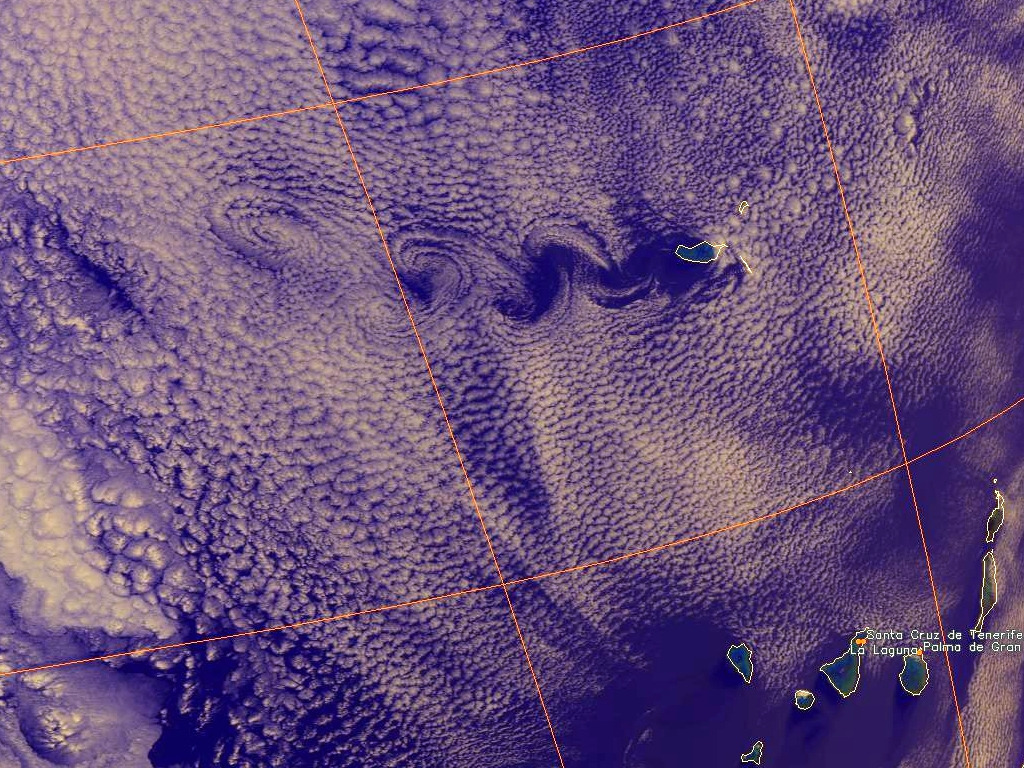

Kármán vortex streets first develop as horizontal oscillations of the air behind isolated obstacles such as small islands in the sea. The lee side air stream rapidly becomes unstable and forms eddies. Upon reaching the obstacle the low level winds are deflected to both sides of the island instead of passing over it. The vortices are visible only if low level cloudiness is already present (figure 1); formation of clouds inside the vortices is rare.

Figure 1: A Kármán vortex street has formed in the lee of Madeira. Metop-A image (VIS0.6, VIS0.8, IR11.0) from 22 February, 2011.

Kármán vortices (or vortex streets) are wave phenomena which have some characteristics in common with waves generated by a Kelvin-Helmholtz (K-H) instability, but unlike all wave types discussed so far, they are not gravity waves. Their main similarity with K-H waves is the strong wind shear which builds up on both sides of the obstacle and the tendency of the generated waves to break. Kármán vortex streets involve two "K-H instabilities" which generate breaking waves with opposite swirls.

The physical process involved in the formation of Kármán waves is similar to the one that makes flags flutter in the wind. The air behind the flagstaff is perturbed and starts to oscillate. With time, the amplitude of the oscillations increases and the formerly stable lee eddies begin to separate and move downwind. Cyclonic and anticyclonic lee eddies form alternatingly downwind of the obstacle (figure 2).

Figure 2: Animation representing the two-dimensional flow patterns behind a rounded obstacle, known as a Von Kármán vortex street. © Cesareo de La Rosa Siqueira

The animation above shows the formation of a Kármán vortex street behind a cylindrical object. The air stream passing right of the cylinder will create cyclonic lee eddies, while the air passing left of it creates anticyclonic eddies. The oscillation of the air current behind the cylinder generates alternating cyclonic and anticyclonic eddies.

Kármán vortices are formed in a layered troposphere. In the boundary layer below 850 hPa wind speeds are usually smaller than in the 'free atmosphere'. An inversion often separates these two layers and prevents any mixing. Such inversions often occur in the vicinity of high pressure systems.

For islands to produce Kármán vortices they have to be high enough to penetrate the inversion. The height of the temperature inversion is particularly important because it determines whether the air flows more easily around the island or over it. Typically wind speeds of 5 to 15 meters per second in the lowest layer are necessary for vortices to form. These conditions are most frequently met in the trade wind regions.

Once the vortices have formed they follow the guiding airflow and dissolve when friction on the ocean surface dissipates rotational energy. Both vortices (cyclonic and anticyclonic) increase in diameter downwind of the obstacle, which results in the conical pattern of the Kármán vortex street. This pattern was first discovered in 1962 with the help of the American weather satellite TIROS V, before which it had been undetectable in the atmosphere.